By understanding the movement patterns and behaviour of yellow sugarcane aphid (YSA), future research and pest control practices can be tailored to reduce the impact of YSA on sugarcane crops. A typical example could be the timing of insecticide applications to target YSA as they begin moving between plants.

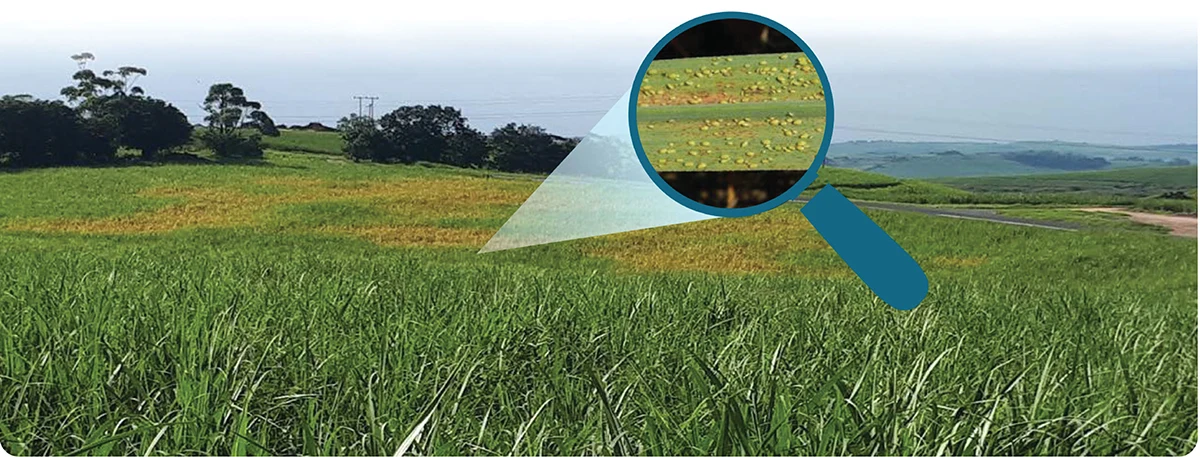

Since the first official recording of YSA in South Africa in 2013, much work has gone into understanding its physical features and genetic makeup. However, gathering information related to aspects of the pest’s biology and how it interacts with the environment is still in the early phases. One such aspect involves the timing and distance of YSA’s movement between plants. Field observations reveal rapid fluctuations in levels of infestation, without any obvious link to weather or farming practices. While much of these observations have been anecdotal, a similar trend appears to exist wherever YSA is a problem in sugarcane.

A study undertaken at SASRI closely monitored YSA colonies under greenhouse conditions to observe movement, changes in feeding behaviour, and development of winged aphids. Key findings from two years of study confirm that YSA moves from plant to plant via the plant canopy (upon canopy closure) and moves between plants via a marching action on the ground. Ground movement was only associated with adults and late instars, and movement was observed at a maximum of four metres at a time before the aphids rested or dispersed. Movement of YSA between plants was most prolific in the late afternoon into the evening, implying a level of sensitivity to sunlight. Temperature fluctuations did not appear to affect movement between plants. However, there was a link between the level of plant stress and movement: 24-38 day old aphids showed more movement away from infested to uninfested plants where more damage was incurred on leaves by growing aphid colonies. Less than 5% of each population during each round of the study developed wings. YSA behaviour appeared also to have been influenced by both biotic (mites, scale, hoverfly) and abiotic (chemical residues) stressors, which was evidenced by reductions in movement and reproductive vigour upon exposure to these stressors.

A study undertaken at SASRI closely monitored YSA colonies under greenhouse conditions to observe movement, changes in feeding behaviour, and development of winged aphids. Key findings from two years of study confirm that YSA moves from plant to plant via the plant canopy (upon canopy closure) and moves between plants via a marching action on the ground. Ground movement was only associated with adults and late instars, and movement was observed at a maximum of four metres at a time before the aphids rested or dispersed. Movement of YSA between plants was most prolific in the late afternoon into the evening, implying a level of sensitivity to sunlight. Temperature fluctuations did not appear to affect movement between plants. However, there was a link between the level of plant stress and movement: 24-38 day old aphids showed more movement away from infested to uninfested plants where more damage was incurred on leaves by growing aphid colonies. Less than 5% of each population during each round of the study developed wings. YSA behaviour appeared also to have been influenced by both biotic (mites, scale, hoverfly) and abiotic (chemical residues) stressors, which was evidenced by reductions in movement and reproductive vigour upon exposure to these stressors.

Ants (Lepisiota capensis) were found in abundance around YSA colonies, however, the ants were not observed moving nymphs around. The relationship between the ants and the YSA is not clear at this stage. The ant/YSA interaction is one that has been consistently observed in commercial cane fields, with not only Lepisiota species but also Linepthema, Tetramorium and Lasius species. It is currently unknown whether a synergistic relationship exists between the two species or whether it might be a case of “mistaken identity” where the ants expect the YSA to produce honeydew (food source for ants), which is a phenomenon that has not been observed in South African cane. A possible next step would be to monitor ant/YSA interactions over a short period of time under controlled conditions.